Table of Contents

Teaching Grammar Creatively

Introduction

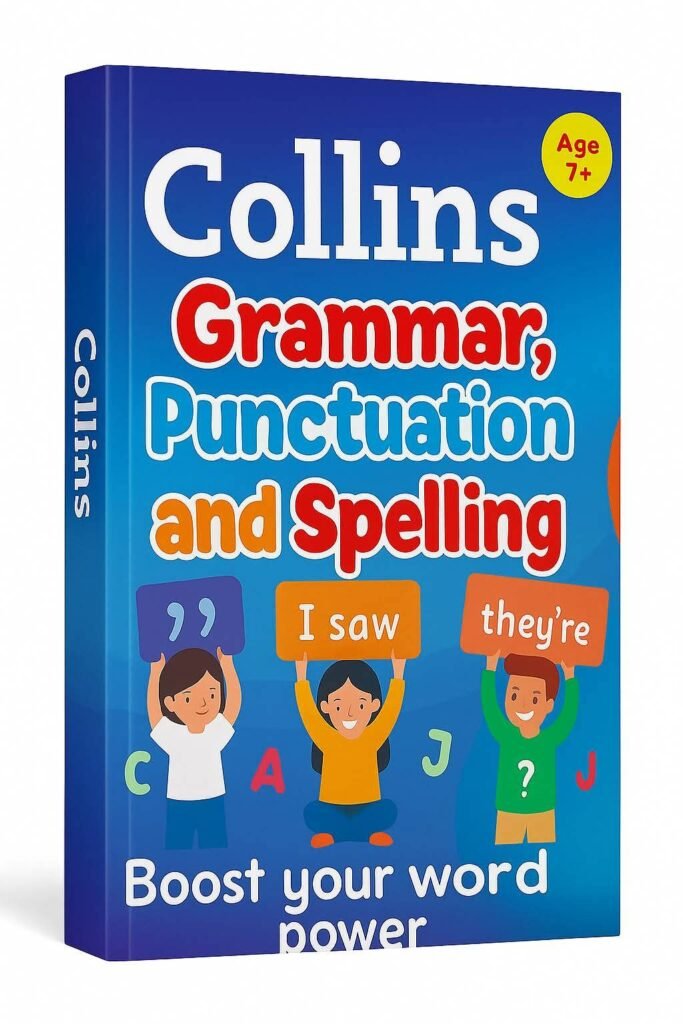

Grammar often feels abstract or tedious to students, especially at the primary and secondary levels. However, research and classroom experience show that creativity is key to making grammar engaging and memorable. A creative approach “can help make complex concepts more digestible and enjoyable for students,” integrating varied activities like role-play, storytelling, games, and technologyjournal1.uad.ac.id. By engaging students in active, playful tasks, teachers make learning both fun and meaningful, which boosts motivation and retentionjournal1.uad.ac.idjournal1.uad.ac.id. For example, using interactive games or stories turns grammar practice into a low-stress, relevant experience; students correct their own errors and internalize rules while collaborating with peersjournal1.uad.ac.idjournal1.uad.ac.id. In this book, each chapter focuses on a specific grammar topic and shows how to teach it with innovative, research-supported methods. We include clear explanations, step-by-step lesson ideas, hands-on activities, differentiation tips, and assessment tools. Our goal is to equip teachers with engaging strategies and practical resources so that every student can learn grammar confidently and creatively.

Chapter 1: Parts of Speech

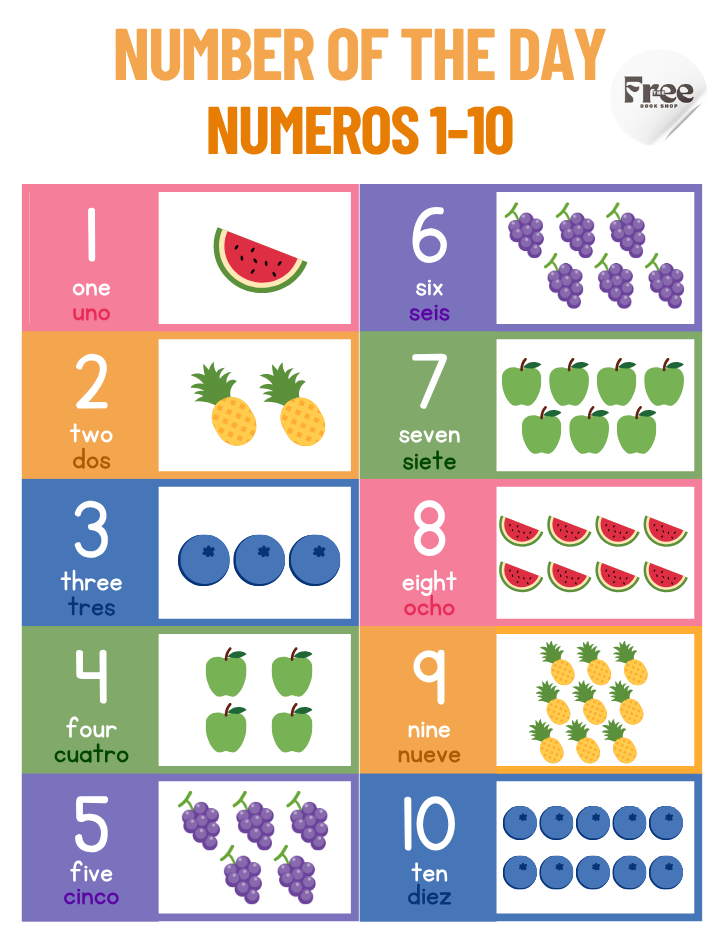

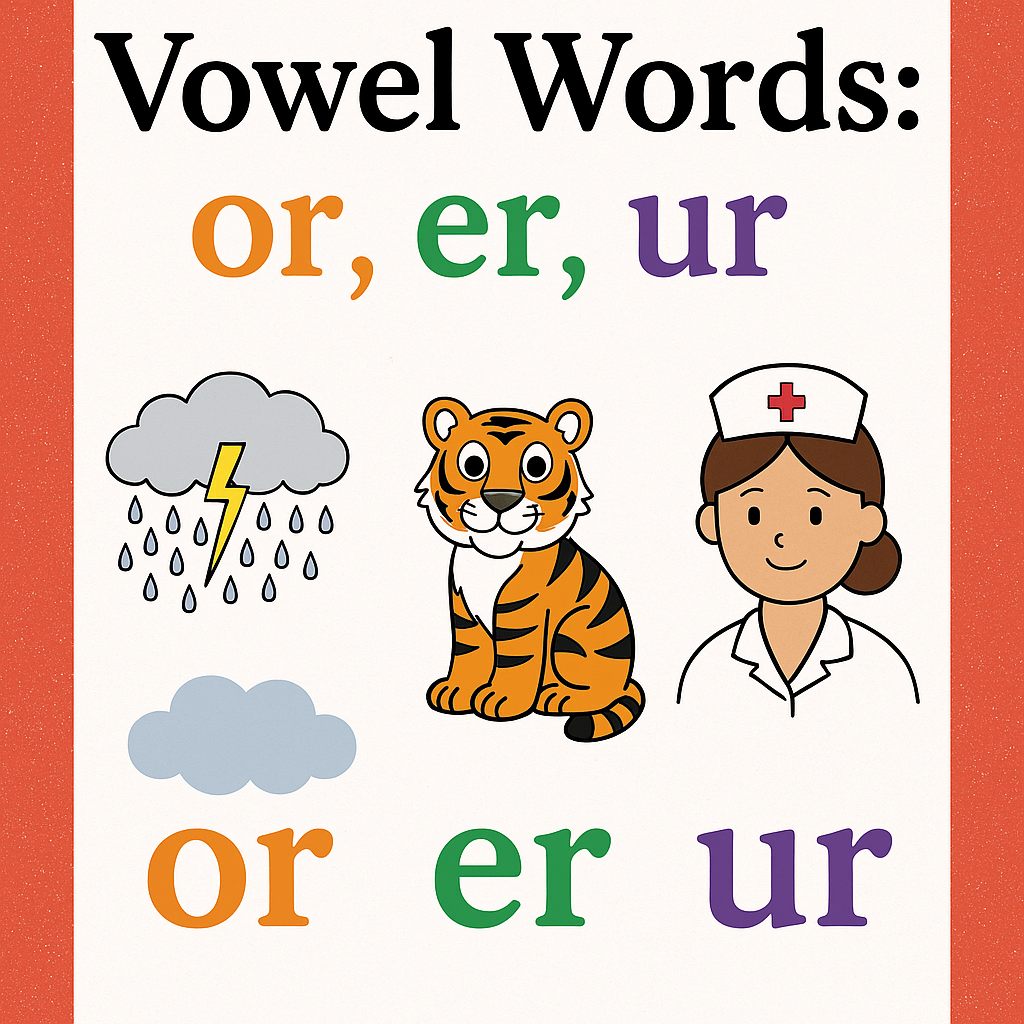

Overview: The parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, etc.) are the building blocks of language. Students must identify and use each part correctly to write and speak with clarity. Introduce parts of speech in context rather than in isolation. For example, start with a story or picture and highlight one part of speech at a time. Teaching each type separately helps beginners grasp the concept, but also show how they work together (e.g. adjectives describe nouns)teachingmadepractical.com. Anchor charts and color-coded posters are useful visuals. Teachers might create a Parts-of-Speech Chart with illustrations or allow students to decorate a classroom word wall with examples of each category.

Creative Strategies: Use a variety of active methods to reinforce each part of speech. For verbs, play Charades: have students pantomime actions while others name the verb. For adjectives, ask learners to bring a favorite object and describe it, prompting use of color, size, and other descriptors. Games are especially effective: bingo with noun/verb/adjective cards, Snakes & Ladders or dominoes adapted for parts of speechjournal1.uad.ac.idteachingenglish.org.uk, and memory/matching games (e.g. match a noun to an image). A card game might show a sentence with a blank and cards of different word types to fill the gap. Storytelling helps too: tell a simple story with exaggerated emphasis on one part of speech, then ask students to retell it highlighting that grammar point (e.g. an “adjective adventure” with lots of describing words). Teachers can record themselves using the target part of speech in a short anecdote, play it back, and then analyze the language togetherteachingenglish.org.uk.

Figure: A visual infographic illustrating typical English adjective order (opinion, size, age, etc.). Using such graphics or anchor charts can help learners remember abstract rules.

Use manipulatives and visuals. Colored chips or Cuisenaire rods can represent different parts of speech: for example, lay out rods in a sentence formation and use different colors for nouns vs. verbsteachingenglish.org.uk. Real objects (realia) work well: to teach countable vs. uncountable nouns, bring in food or toys and sort them into categoriesteachingenglish.org.uk. You can also project students’ own photos (e.g. family pictures, pets) and have them describe them aloud, practicing relevant parts of speech (e.g. “This is my grandmother who… (relative clause), or “I have had this toy since…”teachingenglish.org.ukteachingenglish.org.uk). Graphic organizers (word sorts, anchors) let students manipulate language physically. For instance, give students strips of paper with scrambled sentences and have them rearrange them while identifying each word’s part of speech.

Sample Lesson Plan (Nouns vs. Verbs):

-

Aim: Students will distinguish nouns from verbs in a sentence.

-

Materials: Picture cards (people, animals, objects), “action” cards (drawings of running, eating, etc.), whiteboard.

-

Hook: Show an illustrated scene (e.g. a park with children playing). Ask: “What do you see?” Students name things (dogs, ball, trees – nouns) and actions (playing, sitting – verbs).

-

Teaching: Explain that nouns name people/things and verbs show actions. Write a simple sentence from the picture on the board (e.g. “The dog runs”). Underline the noun (dog) and verb (runs) and label them. Play a short teacher monologue or story including new sentences, then ask students to identify nouns and verbs in itteachingenglish.org.uk.

-

Activity: Noun/Verb Bingo: Give each student a bingo card with 3×3 words (mix of nouns and verbs). Call out a definition or show an image (e.g. show a picture of a cat – “Write meow with your voice”). Students mark “cat” if present. Call out actions too (e.g. “I fly like a bird” for “fly”). First to get bingo wins. This reinforces the difference in a fun wayjournal1.uad.ac.id.

-

Wrap-Up: In pairs, students draw one noun and one verb from a bag and write an original sentence using both. They share with the class. The teacher listens for correct use. Provide feedback and highlight examples.

Differentiation Tips: Tailor activities to each learner’s level. Group students flexibly by ability or learning stylegrammarflip.com. For example, ELLs or struggling learners can work on identifying a few basic nouns/verbs using picture cues, while advanced students can form complex sentences using multiple parts of speechgrammarflip.com. Provide scaffolding: use visual labels (post word cards on a bulletin board under headings Noun, Verb, etc.), sentence frames, and one-on-one support. For kinesthetic learners, have them act out verbs (Simon-says style) or walk around and “find” nouns in the classroom. For visual learners, use color-coding (write nouns in blue, verbs in red). Multi-modal learning is key: combine auditory (songs about grammar), visual (charts, infographics like Figure 1 above), and kinesthetic (clap or move on verbs vs. stand still on nouns)prodigygame.comgrammarflip.com. Peer support helps: pair stronger and weaker students for peer-learning gamesgrammarflip.com. Always allow multiple ways to demonstrate understanding – e.g., speaking, acting, drawing, or writing. According to educational research, a differentiated classroom “presents the same key content but in different ways” so that all students can access itcolorincolorado.orggrammarflip.com.

Assessment: Check understanding informally through the activities above (observe student discussions in the bingo game, note who identifies parts correctly). For a formal check, give a short exit ticket: a sheet with 4 sentences where students must underline or label the noun and verb in each. Alternatively, use a quick quiz on mini-whiteboards: flash a sentence and have students write “N” and “V” under the words. Writing assignments also serve as assessment: ask students to write a paragraph describing a favorite person or place, then highlight or color-code each part of speech they used. For ESL learners, you might provide word banks or allow first-language support. Provide sentence frames (e.g., “The ___ (noun) likes to ___ (verb)”) to help students produce examples. Use rubrics that focus on correct usage of target parts of speech when evaluating written work.

Resources: Supplement lessons with printable worksheets and games. Many online sites (e.g. K12 Reader) offer free Parts-of-Speech exercises. Teachers can create or download flashcards and printable board games (for example, a “parts of speech board game” where players move along by answering questions). See Appendix for sample worksheets (e.g., “Identify the adjective” or “Sort the words by part of speech”). Interactive digital tools (Quizlet flashcards, Kahoot quizzes, grammar apps) allow students to practice parts of speech individually or in teams with immediate feedbackjournal1.uad.ac.id. Remember, using technology is most effective when integrated with creative classroom tasks – for instance, after a storytelling activity, students could play an online noun-verb matching game to reinforce the lesson.

Chapter 2: Sentence Structure

Overview: Once students know the parts of speech, they learn how to combine words into sentences. Teach sentence structure step by step: start with simple sentences (one subject + one predicate), then compound sentences (using connectors like and, but), and finally complex sentences (with subordinate clauses). Emphasize word order (Subject-Verb-Object for English) and punctuation for sentences. Use the Reed–Kellogg or tree-diagram method sparingly as a visual tool to show relationships (simple drawn trees or rails on the board). Frame this chapter around meaning: explain that the goal is to convey clear ideas, whether short or long.

Creative Strategies: Turn sentence-building into a game or story. For example, play Sentence Scramble: write words (including some wrong or extra ones) on cards; teams race to arrange cards into a sensible sentence. Challenge students to avoid a common construction: e.g., have a contest to rewrite sentences without using to be, or to expand simple sentences by adding adjectives/adverbsnowsparkcreativity.com (see EdWeek’s “seven strategies” for inspiration). Use shaped writing: give students a sentence starter in the form of a shape on paper (a spiral for a complex sentence, a dot for simple) and have them complete it – physically guiding how long or short to make the sentencenowsparkcreativity.com. Story-telling again helps: ask each student to add one sentence at a time to a class story, encouraging varied sentence lengths. The collaborative story will naturally include simple, compound, and complex forms if guided.

Use visual aids like sentence strips or chart paper. Write one sentence on a strip and cut it into parts; have students reorder the strips to form a correct sentence. Or use a large paper timeline/flowchart: place subjects on the left, predicates on the right, and draw lines or connectors for compound parts. Color-coding words by role can help: for example, write all subjects in green and verbs in red. Build a “Sentence Wall” where students contribute sentences they create, labeled by type (simple, compound, complex). Grammar games from the previous chapter can be adapted: e.g., in Snakes & Ladders, instead of words, use cards that require forming a certain sentence type to move.

Sample Lesson Plan (Simple vs. Compound Sentences):

-

Aim: Students will combine simple sentences into compound ones using conjunctions.

-

Materials: Pre-written simple sentences on index cards, large Venn-diagram poster (to compare ideas), list of conjunctions on board.

-

Hook: Give each student a card with a simple sentence (e.g. “The cat slept.”; “The dog barked.”). Have them stand up and mingle, then pair up two cards that are about similar subjects or actions. Read each pair aloud.

-

Teaching: Show how to join two related simple sentences using and, but, or so. For example, join “The cat slept.” and “The dog barked.” into “The cat slept and the dog barked.” Discuss when to use each conjunction. Write examples on the board and circle the conjunction.

-

Activity: Conjunction Relay: Divide class into two teams. Post two baskets at one end of the room – one labeled and, the other but. Place piles of simple-sentence cards at the other end. A student runs, grabs two cards, and quickly writes a compound sentence on the board using the correct conjunction basket. The team earns a point if the sentence is correct in grammar and meaning. Rotate until all cards are used.

-

Wrap-Up: On mini-whiteboards, students rewrite a given paragraph by combining adjacent simple sentences into a mix of compound forms, exchanging boards to peer-check each other’s conjunction usage. Discuss as a class why certain connectors were chosen.

Differentiation: Use sentence frames and models. For ESL learners, provide bilingual word banks for conjunctions and connectors. Beginners can start with sentence-building strips (arrange subject-card + verb-card + object-card) before moving to full writing. Visual supports (flowcharts, diagrams) clarify sentence parts and can be referred to during writing. Flexible grouping is useful: provide stronger readers with complex-clause activities (e.g. adding subordinate clauses with when, because, if), while others work on simple sentences firstgrammarflip.comcolorincolorado.org. Offer choices: some students might create a short skit (speaking) that uses different sentence types, while others write examples. Multi-sensory options: have students act out parts of a compound sentence (one student says the first clause, another says “and/but/so”, another says the second clause) to reinforce structure.

Assessment: Evaluate sentence skills through writing and speaking tasks. A quick formative assessment is to give each student a pair of simple sentences and ask them to write a combined sentence. Check that they use an appropriate conjunction and proper punctuation. Peer editing can be used: give students short paragraphs written by classmates with missing punctuation or connectors, and have them correct the sentences. Use exit tickets: e.g. “Rewrite this run-on sentence using and or but: ‘I wanted to play we stayed home.’” For longer-term assessment, assign a short creative writing piece (a story or diary entry) and review the variety of sentence structures used; provide feedback on clarity and correctness. Use rubrics that reward increasing complexity and correct grammar. Keep encouraging creative output: praise students when they experiment with new sentence forms.

Resources: Printable sentence-building worksheets (jumble puzzles, sentence-completion exercises) can be used for practice. Online sentence games (e.g. SentencePlaysentenceplay.co.uk) let students drag words into place. Whiteboard apps and digital story-building tools allow collaborative practice. There are many free sentence construction templates (e.g. simple mad libs with blanks for parts of speech to combine into sentences). A helpful project-based idea is to have students create a “Grammar Book” or booklet where they draw a short comic strip and write complex sentences as captions, combining visuals with language.

Chapter 3: Punctuation

Overview: Punctuation marks are the “road signs” of writing, showing stops, questions, excitement, pauses, and more. Teach students each punctuation mark’s function in context. For example, read a sentence aloud with different intonation for a period (.), question mark (?), or exclamation point (!). Emphasize that punctuation changes meaning: e.g. “Let’s eat, Grandma!” vs. “Let’s eat Grandma!”. Start with end punctuation (sentence-final) and then cover others (commas, quotation marks, apostrophes, etc.). Use the context of the sentence’s meaning and structure to explain each mark.

Figure: Infographic on end-of-sentence punctuation (period, question mark, exclamation). Visual charts or infographics like this one help students remember when to use each mark.

Creative Strategies: Treat punctuation as a game of emphasis and expression. For example, give students short dialogues and ask them to add punctuation so that the meaning changes: “Watch out” can become a statement or a command depending on the mark. Play Punctuation Detective: give groups of students a paragraph with missing punctuation and have them race to insert the correct marks. Use dictation games: prepare a fun story and read it aloud without writing it on the board. Students work in teams; one student listens, writes the sentence as they hear it, then the team adds punctuation. When the story ends, compare results to the original text. This is a form of wall dictation, which is often lively and interactiveteachingenglish.org.uk.

Use visual and kinesthetic tools. For teaching commas and lists, give each student a picture (e.g. of fruits) and have them stand in a line to form a sentence: “Tom has apples, bananas, and cherries.” Each student says a word and passes a ball (comma) between them. Punctuation marks can be color-coded (e.g. blue periods, red question marks) on the board. Storytelling with emphasis also teaches punctuation: have students pantomime emotions (surprise, excitement) as you narrate, corresponding to exclamation marks. Use graphic organizers: e.g. a “Punctuation Poster” illustrating each mark with a definition and cartoon examples.

Sample Lesson Plan (Comma Use):

-

Aim: Students will use commas in lists and to separate clauses.

-

Materials: A short paragraph on strips (without commas), index cards labeled “

, (comma)” and “. (period),” large poster of the Punctuation Infographic (Figure above). -

Hook: Act out a short funny sentence without punctuation, pausing oddly: “I bought apples oranges bananas and grapes”. Students guess what was confusing. Show the sentence on the board without commas.

-

Teaching: Explain that commas separate items or clauses. Revise the sentence on the board: “I bought apples, oranges, bananas, and grapes.” Ask why commas help. Go through the strips of the paragraph sentence by sentence, discussing where a pause or breath naturally goes (often before

and, after a long phrase). -

Activity: Punctuation Relay: Form teams and give each team a copy of a jumbled short paragraph (no punctuation). Place piles of comma cards, period cards, and question/exclamation cards at one end. One member at a time runs, picks the next punctuation needed (based on meaning and pauses), and attaches it to the board. Teammates discuss and decide. First team to correctly punctuate their paragraph wins a round.

-

Wrap-Up: On mini-whiteboards, students write one sentence from the activity with correct punctuation. Share as a class. Emphasize how the meaning is clearer with commas or question marks.

Differentiation: Provide sentence strips and checklists for ESL or special-needs students. For example, give them a “Punctuation Mark Chart” with examples (see [Figure] above) or a story map highlighting pauses. Beginners might start with simply adding periods and question marks to dictated sentences. Use pictures to explain context (e.g. point to a puzzled face when teaching question marks). Offer choices in practice: some students may work on sorting cards labeled with sentences and matching punctuation, others may illustrate dialogue using quotation marks on a comic strip. Scaffold by initially focusing on one punctuation type (such as periods) before adding others. Flexible grouping can pair stronger readers with ELLs during editing exercises; collaborative discussion helps all students notice correct punctuation. Remember that students “do not need to be taught individually; differentiating is a matter of presenting the same task in different ways”colorincolorado.org.

Assessment: Use editing exercises for assessment. For formative checks, present sentences or short paragraphs with missing or incorrect punctuation and ask students to fix them (a quick “find and fix” activity). Response journals can be used: after a reading, students must rewrite a confusing run-on line from the text with proper punctuation. Peer review is useful: have students swap short written pieces and check each other’s punctuation. Summative assessment might involve a writing assignment (story or letter) assessed with a rubric that includes punctuation accuracy. Also use informal checks: for example, give each student a mini-whiteboard and say a sentence aloud. Ask them to write the sentence and underline the punctuation (often done as an exit ticket). Many technology tools (such as grammar blogs, Kahoot quizzes) focus on punctuation practice and give instant feedback, which helps reinforce learningjournal1.uad.ac.id.

Resources: Provide printable punctuation worksheets and activities. For example, one worksheet may list everyday commands or exclamations with blanks for punctuation. Websites offer interactive punctuation tutorials. Digital tools like interactive punctuation drag-and-drop games can engage tech-savvy learners. A creative project could be to have students design a “Punctuation Poster” illustrating all marks with examples – this doubles as a visual aid in class. A useful handout (see Appendix) is a “Punctuation Rules Reference Sheet” summarizing key guidelines. Many teacher forums and sites (e.g. British Council) have downloadable punctuation games (e.g. punctuation bingo cards, dice games) for classroom useteachingenglish.org.uk.

Chapter 4: Verb Tenses

Overview: Verb tenses allow students to talk about time: events that already happened, things happening now, or those that will occur. Begin with concrete real-life connections: a timeline on the wall can help students place actions in “Past, Present, Future” with pictures (e.g. yesterday’s photo, today’s photo, tomorrow’s calendar). Explain the basic forms (past, present, future simple) and gradually add others (past progressive, present perfect, etc.) as appropriate for grade level. Use clear examples and relate them to students’ own experiences (“Yesterday I played… Tomorrow I will… by next year I will have…”).

Creative Strategies: Storytelling and role-play are powerful for practicing tenses. Have students create and act out a “time-travel play” where characters visit the past and the future, using past and future tense dialogs. Turn a history or science lesson into grammar practice by having students recount it in different tenses (e.g. “Dinosaurs roamed the Earth millions of years ago” vs. “Next class, we will explore fossils”). Games and songs reinforce tenses naturally: teach a past-tense song (many kids’ songs use past tense) and have students identify all verbs, or sing the same song changing it to future tense. For example, if teaching past tense, students might list “I went, I saw, I did…” in a chant. Use a verb tense “timeline game”: give each student a sentence card (e.g. “play,” “ran,” “will jump”) and they place themselves on a life-size line on the floor for Past, Present, or Future.

Use visual aids liberally. A cartoon or comic strip works well: show a simple three-panel cartoon (past, present, future scenes) and have students caption each panel using correct tense. Infographics like the one below (a timeline of tenses) can make abstract forms concrete. Tense charts with color-coding help students spot patterns (e.g. yellow for past forms, green for present). Incorporate technology: grammar apps like Quizlet have verb tense flashcards and games. Websites like Duolingo or Quizziz offer tense practice with immediate feedbackjournal1.uad.ac.id.

Sample Lesson Plan (Past vs. Past Continuous):

-

Aim: Students will use past simple and past continuous to describe events.

-

Materials: A short video clip (e.g. cartoon) without sound, sentence strips, anchor chart of verbs in -ed and was/were forms.

-

Hook: Show a brief silent video of a simple scene (e.g. a cat chasing a mouse while it is eating). Ask students: “What was happening?” and “What happened after?” Elicit answers in present tense (it is chasing, it is eating).

-

Teaching: Explain the past continuous (“was/were + verb+ing”) for ongoing actions, and past simple for completed actions. Show the video again; this time narrate using past tense: “The cat was chasing the mouse when the mouse ate a piece of cheese.” Write this sentence on the board. Circle was chasing and ate, labeling their forms.

-

Activity: Tense Theater: In small groups, students improvise a short skit using prompts on cards (e.g. “While I ____, I saw a ____”). Each group uses at least one continuous and one simple past in their lines. Groups perform while others identify the tenses used.

-

Wrap-Up: Students complete an interactive worksheet: given sentence fragments (e.g. “The teacher / explain (past simple) the lesson / the students (past continuous) / take notes.”), they must form a full sentence: “The teacher explained the lesson while the students were taking notes.” Share answers as a class.

Differentiation: Provide verb charts and lists to ESL learners – for example, a notebook “cheat sheet” of common verbs in present/past forms. Use visuals like timelines or color bars to illustrate tense changes. For kinesthetic learners, have them act out verb tenses (e.g. walk slowly while acting out “was walking,” freeze for “stood”). Struggling writers can be allowed to write verbs on word banks or fill-in-the-blank templates first. Offer leveled activities: while some students form sentences with simple tenses, others can practice perfect or continuous forms. Flexible grouping works: peer-tutoring pairs can practice dialogues together, with stronger students modeling tense forms. Multimodal tasks (drawing, speaking, moving) ensure that “a lesson resonates with more students if it targets visual, tactile, auditory and kinesthetic senses”prodigygame.com.

Assessment: Use both written and oral assessments. A common formative strategy is the “timeline writing”: ask students to list three things they did yesterday (past tense) and three things they will do tomorrow (future tense), and check for correctness. Collect journals or exit cards where students write a few sentences about an illustrated story in past tense. During speaking activities (like Tense Theater), note each student’s usage. A quick low-tech check: hold up two thumbs-up/down cards and say a sentence (“I was writing”). Students show thumbs up if correct, down if not. For summative assessment, include tense-focused questions in grammar quizzes and require correct verb forms in writing tasks. Provide rubrics that give feedback on tense consistency and form accuracy.

Resources: Many online worksheets target verb tenses (e.g. fill-in-the-blank exercises, matching timelines). Use apps like Quizlet or Kahoot! (as noted by Tamam, “gamified platforms” give immediate feedback on grammar)journal1.uad.ac.id. English-teaching blogs offer free resources (e.g. tefltastic’s tense review worksheets). Encourage project-based learning: for example, older students can create short video diaries (present tense) or historical news reports (past tense), integrating grammar with creative media. Appendixes may include printable timeline organizers or tense chart handouts for classroom use.

Chapter 5: Differentiating Grammar Instruction

Overview: Classrooms are diverse. Students have different abilities, backgrounds, and language proficiencies. Differentiated instruction means presenting the same grammar content in multiple ways so all learners can access it. As one expert notes, differentiation is not teaching different lessons for each child, but giving “every student the same key content, but [allowing] them to approach it in their own ways”colorincolorado.org. Factors like readiness (skill level), interests, and learning profile guide our choicescolorincolorado.org. In grammar teaching, this might mean providing extra support for ESL students or advanced challenges for gifted writers, while keeping everyone working toward the same grammatical goals.

Strategies: Key approaches include flexible grouping, scaffolding, and multimodal teaching.

-

Flexible Grouping: Group students by skill or learning style for certain activitiesgrammarflip.com. For example, form a reading group of ELLs who focus on vocabulary and grammar foundations, while others work on advanced editing tasks. Groups should be fluid: change them as needed so students learn from different peersprodigygame.com.

-

Scaffolding: Break complex grammar tasks into smaller stepsgrammarflip.com. For instance, when teaching clause structures, start with identifying subjects and verbs before combining clauses. Provide sentence starters or outlines for students who need them. Use visuals such as color-coding or charts to break down grammar rules. Gradually remove supports as students gain confidence.

-

Multimodal Learning: Offer varied ways to learn. Use visual aids (charts, posters, infographics) for spatial learners, music and chants for auditory learners (e.g., a rhythmic rap of irregular verbs), and hands-on activities (sorting cards, role-play) for kinesthetic learnersprodigygame.comgrammarflip.com. Present grammar points through stories, songs, or art projects as well as traditional texts. For example, an ESL student might learn possessive ’s by assembling a family photo album and labeling pictures (“Maria’s cat,” “boys’ soccer ball”) – mixing language with personal interest.

-

Choice and Personalization: Let students choose assignments that match their interests. If learning prepositions, one student might write about travel (using a map), another about sports (drawing a playbook). Incorporating real-world context engages all learners: give ELLs or struggling students meaningful content (like a recipe or game instructions) to see grammar at workgrammarflip.com. Project-based tasks (writing a newspaper, planning a class party) naturally differentiate as students take on roles suited to their strengths.

-

Ongoing Assessment: Use formative checks to guide differentiationcolorincolorado.org. For example, a quick grammar quiz or exit ticket can show which students need more practice. Adjust homework and activities accordingly: advanced students might have enrichment tasks (finding examples of passive voice in literature), while others get more practice worksheets or oral exercises.

Assessment and Feedback: Differentiated assessment means giving students multiple ways to demonstrate grammar mastery. Beyond written tests, use oral presentations, posters, skits, or digital projects. Encourage self-assessment: have students set their own grammar goals and reflect on progress (e.g., mark their errors on a quiz to learn from them). Provide clear rubrics so each student knows the expectations at their level. Remember, effective differentiation involves continually asking, “What does this student need right now to advance?”colorincolorado.orggrammarflip.com. By adapting instruction and assessment, teachers ensure that all learners – including ELLs and those with special needs – can achieve the same learning objectives in a supportive way.

Chapter 6: Assessing Grammar Learning

Overview: Assessment in grammar should be ongoing and varied. While quizzes and tests are traditional, formative strategies (ongoing checks during learning) are highly effective. For example, quick exercises like exit tickets or “one-minute papers” where students explain what they learned help teachers catch misunderstandings earlynwea.org. The purpose is two-fold: to inform the teacher (What do students still struggle with?) and to inform students (What do I need to review?).

Formative Assessment Strategies: Integrate short, regular checks into lessons. Use mini whiteboards to have students write a corrected sentence or label a part of speech on the fly. Use peer review: have students swap a paragraph and underline each other’s grammar errors. Think-Pair-Share works well for grammar: pose a sentence question, let students think individually, discuss with a partner, then share with class – this engages multiple learners and reveals understandingprodigygame.com. Games as assessment: Activities like grammar Bingo or Jeopardy can double as quizzes. For instance, a grammar “spin the wheel” game could end each round with a quick question or challenge (e.g., “tell us the past tense of ‘build’”).

Summative Assessment: At unit’s end, use a formal test or project. Tests might include editing a passage, writing sentences in specified forms, or multiple-choice questions on usage. Projects (like a writing portfolio or grammar scavenger hunt) let students apply grammar authentically. Rubrics ensure fair grading; they can include criteria like “correct usage of target grammar in context” and “evidence of editing.” Also consider performance-based assessment: for example, have students give a short oral presentation or write a skit that uses certain grammatical structures.

Feedback: Give specific, actionable feedback. Rather than just marking answers right/wrong, point out patterns: “Notice you missed the comma in the introductory clause here.” Encourage self-correction by asking guiding questions (e.g. “Should there be punctuation before and?”). Celebrate success and improvement to build confidence. Use positive reinforcement: grammar can be fun, so praise creative or accurate language use as much as you correct errors.

Resources: Many assessment tools exist. Online platforms like Google Forms or learning management systems allow quick quizzes with auto-grading. Grammar apps can track individual progress over time. Printable checklists and rubrics help students self-edit (e.g. “Did I use capital letters and end punctuation in every sentence?”). An effective strategy is to maintain a grammar journal: students write daily or weekly and revisit earlier entries to identify mistakes they’ve made repeatedly, fostering metacognition (reflecting on their own learning)nwea.org. Provide sample tests or practice exercises (old quizzes, textbook worksheets) so students know what to expect.

Chapter 7: Digital Tools & Resources

Integrating Technology: There are many digital tools that make grammar practice interactive. Quizlet and Kahoot! offer game-like quizzes on parts of speech or tenses – immediate feedback on these “gamified platforms” keeps students motivatedjournal1.uad.ac.id. For example, a Kahoot review can end a lesson with a friendly competition on the day’s grammar point. Interactive websites (Grammar Bytes, British Council LearnEnglish Teens) have puzzles, drag-and-drop exercises, and animated lessons. Mobile apps like Duolingo and Memrise include grammar in context.

Visual and Print Resources: Teachers should curate downloadable resources to save prep time. Good sources include K12Reader, TeachersPayTeachers (some free materials), and educational sites (British Council, Colorín Colorado for ESL strategies). Provide students with printable handouts such as: parts-of-speech charts, tense timelines, punctuation reference sheets, and crossword or matching worksheets for practice. Use graphic organizers like Venn diagrams to compare tenses (Past vs. Present) or storyboards for sequencing events (helping with tense consistency).

Project and Game Resources: Incorporate project-based learning when possible. For instance, students could create a mini “grammar museum” exhibiting their own examples: posters explaining a grammar rule, cartoons illustrating correct vs. incorrect usage, or a video advertisement using persuasive sentence structures. There are also ready-to-print grammar games available – e.g. board game templates (Snakes & Ladders with grammar tasks on squaresteachingenglish.org.uk), card games (Parts of Speech Uno), or bingo sets.

Classroom Helpers: Label classroom objects with nouns and adjectives to give constant exposure. Word walls can have sections for each part of speech or tense verb forms. Audio-visual materials such as songs, short movies, and picture books provide context for grammar points (e.g., using a fairy tale to teach past tense verbs).

Citing and Sharing: Always mention and share useful resources with students and parents. Encourage students to use reputable online grammar checkers (as learning tools, not crutches) and to read extensively – books and articles show grammar in context. Provide a list of suggested websites or apps (Appendix has recommendations).

Appendix: Sample Resources

-

Worksheets: Printable worksheets for each topic (e.g. noun/verb sorting, sentence punctuation exercises, tense identification quizzes).

-

Handouts: Quick reference sheets (parts of speech chart, punctuation rules poster, tense timeline).

-

Game Templates: Blank game boards (e.g. Snakes & Ladders, Dice games) that teachers can customize with their own questions.

-

Activity Ideas: Collections of short activities (e.g. charades prompts for verbs, story starters, exit-ticket formats).

Each of these can be photocopied or adapted for your classroom. By using these creative, student-centered approaches – as supported by educational researchjournal1.uad.ac.idjournal1.uad.ac.id – teachers will turn grammar from a chore into an adventure. Grammar rules will no longer be “just rules,” but tools students use confidently in writing and speaking.

Sources: The strategies and examples here are based on current research and teaching practicejournal1.uad.ac.idjournal1.uad.ac.idteachingenglish.org.ukgrammarflip.comprodigygame.comcolorincolorado.org. The cited literature emphasizes that when grammar instruction is interactive and meaningful, learners are more motivated and retain more informationjournal1.uad.ac.idjournal1.uad.ac.id. Teachers are encouraged to adapt these ideas, experiment, and share their successes – a creative teaching approach benefits everyone in the classroom.